Chewang Norphel, the Iceman of Ladakh

“Mr Norphel!” Chewang heard someone call his name. It was a smiling woman climbing up from the stream. On her back she was hauling a plastic barrel of water that she’d just filled. He recognised her from his previous visit. Since it was his last village stop of the day, Chewang agreed to join her for a cup of tea in her home. As they walked to her yellow mud-brick house, he looked out across the fields of the valley floor. They were brown and bare. It was May, and they should have been green with that year’s crop of barley. Looking upwards, he saw what he had feared. Here, just as in other places he’d visited, the blue-grey glacier above the village had retreated higher up the mountainside.

Inside, as she boiled water for yak butter tea, the woman explained that the stream from the melting glacier had arrived late again that year. Her husband was out irrigating the fields, but she feared it was too late and their crop would fail. Normally peaceful neighbours had been squabbling over water, so they had asked a monk to come and perform a puja – or prayer ritual – to bring water to the village. But perhaps Mr Norphel could do something to help?

It was 1987, and 52-year-old civil engineer Chewang Norphel was visiting some of the 120 scattered villages in Ladakh to check on his projects. In over 20 years working here, he’d helped build almost every school, bridge and road in the region. With his neat hair and warm smile, he was a familiar figure whom everyone loved to see. Recently he had heard about the same problem everywhere he went: water shortages.

Ladakh, meaning ‘land of high passes’ in Tibetan, is an isolated region of northern India. Lying between the Himalayan and Karakoram mountain ranges, at over 3,000 metres above sea level, it is one of the highest inhabited places on earth. Colourful prayer flags flutter above monasteries and gompa, Buddhist temples, dot the bare valley floor overlooked by jagged mountains. While few people live here, many tourists visit each year to enjoy the rich culture and trek in the spectacular scenery.

The region is a high-altitude desert, and temperatures in winter can fall below minus 20 degrees Celsius. It is drier than the Sahara because it lies in the rain shadow of the Himalayas, which means that when air reaches this side of the mountains it has already lost its rain. Ladakh gets as little as 103 millimetres of rain a year and farmers depend on the water from melting mountain glaciers to grow their crops.

Glaciers are slow-moving rivers of ice formed high in the mountains. Layers of snow build up over years and become compacted into ice until they are heavy enough to move gradually down the slopes. Each year in spring the lowest areas of the glaciers melt and run in streams to the valleys below. But global warming means that more of the ice is melting each year, so glaciers are shrinking up the mountainside. Added to this, less snow is falling during the winter to renew them. Ice higher in the mountains melts later in the year as temperatures are cooler there, and for the farmers of Ladakh this meant that there was no water in March or April when they desperately needed it for their newly sown crops. The lack of fresh grass meant villagers were forced to send their goats and sheep into the mountains to graze, where they risked losing them to attacks by lynx and snow leopards. Many families had no choice but to leave the land that had been their home for generations. It broke Chewang’s heart to see people suffering. He had a strong Buddhist faith and believed our time on earth is precious and should not be wasted. He wanted to use his time to help others.

Chewang was born in 1935 and grew up in a farming family in Leh, Ladakh’s biggest town. As a child he helped his parents at home and out in the fields after school. He loved maths and science, and would often scratch out sums in the dirt as he watched the goats. Chewang was inspired by his father’s cousin who had studied in London before becoming Ladakh’s first engineer and building its airport and first roads. But Chewang was the youngest of three brothers and because his family could not afford to send them all to school he was expected to join a monastery rather than go to secondary school. Instead, aged 10, Chewang ran away to Srinagar, 400 kilometres away across the rugged mountain passes, so that he could finish his schooling. While there, he cooked and cleaned for the teachers to pay for his food and a place to stay. He went on to study engineering at university.

On completing his studies, Chewang returned to Leh and immediately got a job working for his father’s cousin as a rural civil engineer. He worked on many government projects and as water shortages began to take effect he was asked to look into building concrete dams to store water. But Chewang realised that dams could be very damaging to the environment and were also expensive to build. He felt sure there must be a better solution to the problem and began to experiment with different ideas. Then one winter morning he had a bright idea . . .

There was a village water tap near his house that was left running throughout winter to stop the pipes freezing. Chewang noticed that as water ran to join the stream, some froze in pools in the shade of a tree. The ice pools grew bigger by the day, but meanwhile the fast-running stream flowed freely without freezing over. In spring, the pools of ice gradually melted away. Chewang wondered if there was a way to slow down the fast-running mountain streams to create shallow pools where water could be frozen and stored in the winter and then melted in spring. What if he could make artificial glaciers?

Chewang was excited by this idea and began to sketch some designs. Streams would be gently slowed by a series of walls until the water froze, little by little, as an artificial glacier. Wide streams would form frozen waterfalls as they made their way down the mountainside, while narrow streams on steeper slopes would first be diverted along a channel to a gentler incline. He would try to build his glaciers in the shade of the mountain, and always make sure they were as close as possible to the village so the ice would melt early enough in spring to irrigate the precious crops.

When Chewang showed his idea to villagers and officials to ask for funding, they called him pagal, or crazy. The idea of artificial glaciers was just too strange for them to understand. But in 1987, undeterred, and with only a few people to help him, he built his first experimental glacier in a valley above the village of Phutskey. As soon as winter ended, he hiked up to the valley and was delighted to see it covered in a sheet of ice. When the ice melted that spring, the villagers were so amazed and happy to have water that they later helped him build the walls and channels to make an even bigger glacier, to provide more water the following year.

In 1995, Chewang retired from his job, but he was not satisfied with staying at home. The water shortages were being made worse in Leh by the increased number of tourists, who expected showers and flush toilets which used up precious water from underground. Water was being trucked into the city and the harvest had been so poor that there had been grain rationing. Chewang wanted to put his engineering skills to good use, so he took a position as head of a charity called the Leh Nutrition Project and threw himself into helping as many villages as he could by building artificial glaciers.

Over the next 20 years, Chewang built 14 more artificial glaciers in Ladakh. While he managed to get funding from the Indian government and not-for-profit organisations, the biggest challenge was often getting villagers to support his ‘crazy’ project. The glaciers had to be created differently depending on the landscape and available shade, and Chewang needed their local knowledge to plan each one. But even in his seventies he still liked to hike up and camp overnight in the mountains to get to know the area himself.

Once local people understood how artificial glaciers could help them, they were happy to get involved. Without easy access to machinery and equipment, work was mostly done by hand using labourers and volunteers. Sometimes the whole village would help, including grandparents, although it often meant carrying building materials on their backs through steep terrain and working with the ever-present danger of rockfalls.

Chewang has transformed thousands of lives in Ladakh. Over the last 30 years, people have watched their mountains change colour as glaciers vanished, leaving only bare rock. But today, thanks to his artificial glaciers, some villages grow two crops a year instead of one and harvests are larger, which means some produce can be sold. Potatoes and peas now grow well and these fetch more money than traditional barley. Once dry and desolate valleys are looking greener than ever, and villagers no longer have to send their animals into the mountains to graze. Perhaps most importantly, young people, tempted to move away to the cities, can consider staying in farming, keeping families together.

Chewang has earned the nickname ‘Iceman of Ladakh’ and always feels great joy at seeing the impact he has made on people’s lives. His work for communities has been recognised internationally with awards including the Jamnalal Bajaj Award for promoting the values of Gandhi, and the Padma Shri, the fourth highest public award in India.

He still dreams of building new artificial glaciers, although sadly there is not always enough money available to fund them. Now in his eighties, Chewang can often be found at home, spending time with his wife, meditating or gardening. He likes to experiment with new crops – like tomatoes, aubergines, apples and peppers – that might grow in the warming climate and help his fellow Ladakhis.

Artificial glaciers are not a long-term solution for Ladakh because the streams that build them are fed by winter snowfall and this is threatened by climate change. But people have survived in this harshest and most inhospitable of regions for centuries and the project is buying them time. The future of this ancient mountain kingdom is uncertain, but for now, thanks to the dedication of one ingenious and resourceful man, these ancient communities can live and thrive in the land they call home.

About the author

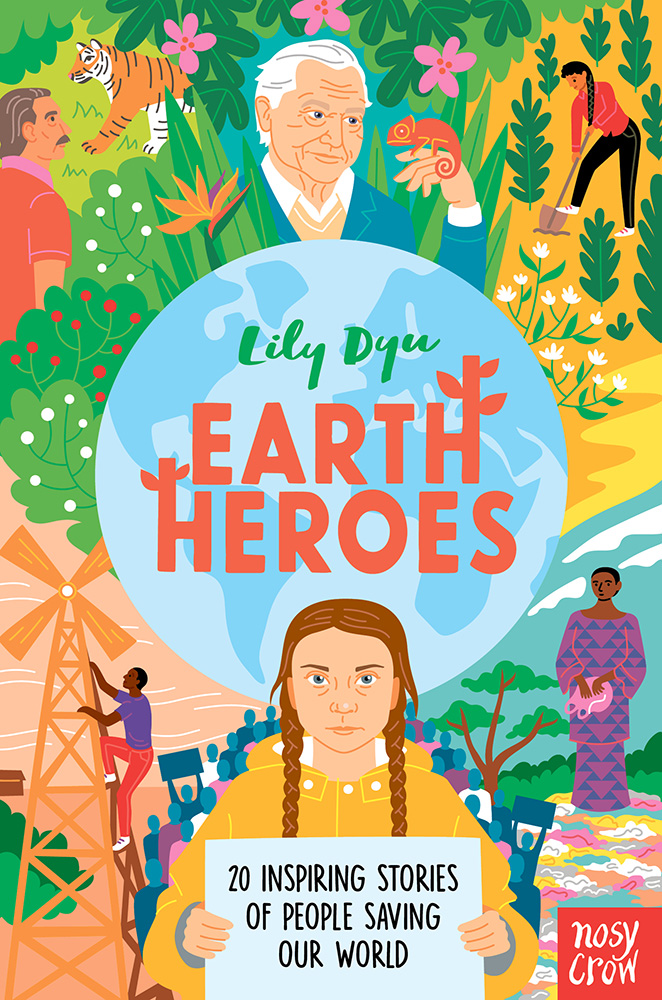

The above story was written by Lily Dyu for her beautifully illustrated book Earth Heroes published by Nosy Crow publishing.

Climate Heroes collaborated with Earth Heroes to publish several of their stories on the website.

Earth Heroes

Publication date: 03 Oct 2019

ISBN: 9781788008525

Size: 138 x 204 mm

Length: 272 pages